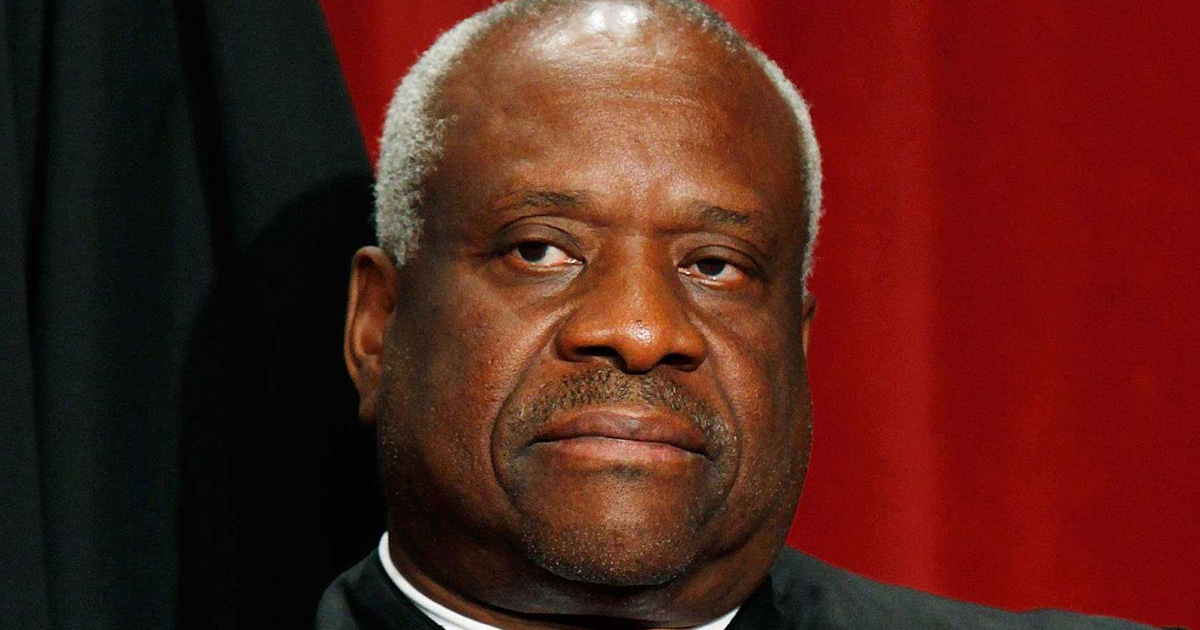

On Monday, the Supreme Court declined to hear Leonard v. Texas, a case related to the civil forfeiture of assets. In the case, James Leonard and Nicosa Kane were pulled over in an identified drug hotbed. In their car was a safe containing over $200,000 and the bill of sale to a home. Police seized the money, believing that it was connected to drug sales, but Kane claims that the money was from selling a house. The Court did not hear the case based on procedural issues, but that did not stop Justice Clarence Thomas from offering a statement condemning the practice of civil forfeiture.

Civil asset forfeiture is the practice where law enforcement officials can seize money and even property from those merely under suspicion of criminal activity. The practice has passed several legal tests, most recently when the Supreme Court ruled in Bennis v. Michigan in 1996. But since then, the system of forfeiture has seen, “egregious and well-chronicled abuses,” according to Thomas.

The only requirement for law enforcement to seize assets is that they have to show that the property is somehow involved in a crime. Since this is a civil matter, there is no due process, no right to a jury, and the burden of proof needed in court is low.

Law enforcement has taken this legal gap and turned it into a profit-making scheme. Justice Thomas cited a study by the Institute for Justice that showed the Department of Justice alone raked in $4.5 billion from forfeitures in 2014. Thomas said, “because the law enforcement entity responsible for seizing the property often keeps it, these entities have strong incentives to pursue forfeiture.”

This policing-for-profit has become an epidemic, with law enforcement agencies crafting policies to increase the amount of property they seize.

Thomas used many examples where police have worked with their district attorney to threaten those under investigation unless they signed over their property. He pointed to a small town in Texas that pulls over out-of-town drivers and works with the DA to coerce them to give up their assets. This practice often places an unfair burden on those that cannot afford legal representation. Thomas pointed out that,

“[t]hese forfeiture operations frequently target the poor and other groups least able to defend their interests in forfeiture proceedings.”

Originally meant to fight piracy and seize ships that avoided taxation, the forfeiture laws have simply not caught up to modern practices. The suspicion of a crime, usually related to narcotics, has allowed police to seize homes, cash, and cars without any judicial oversight. In Bennis, for instance, a man used a car to solicit a prostitute. That car was owned jointly by the man and his wife. Though his wife was innocent, she had no right to due process under the Constitution when it came to keeping the vehicle. But even that case had to cite precedent from a 1827 case involving a Spanish pirate vessel (The Palmyra, 25 US 1).

While the Court had to deny the Leonard case on procedural grounds, Justice Thomas hopes that another similar case comes forward soon:

“Whether this Court’s treatment of the broad modern forfeiture practice can be justified by the narrow historical one is certainly worthy of consideration in greater detail.”