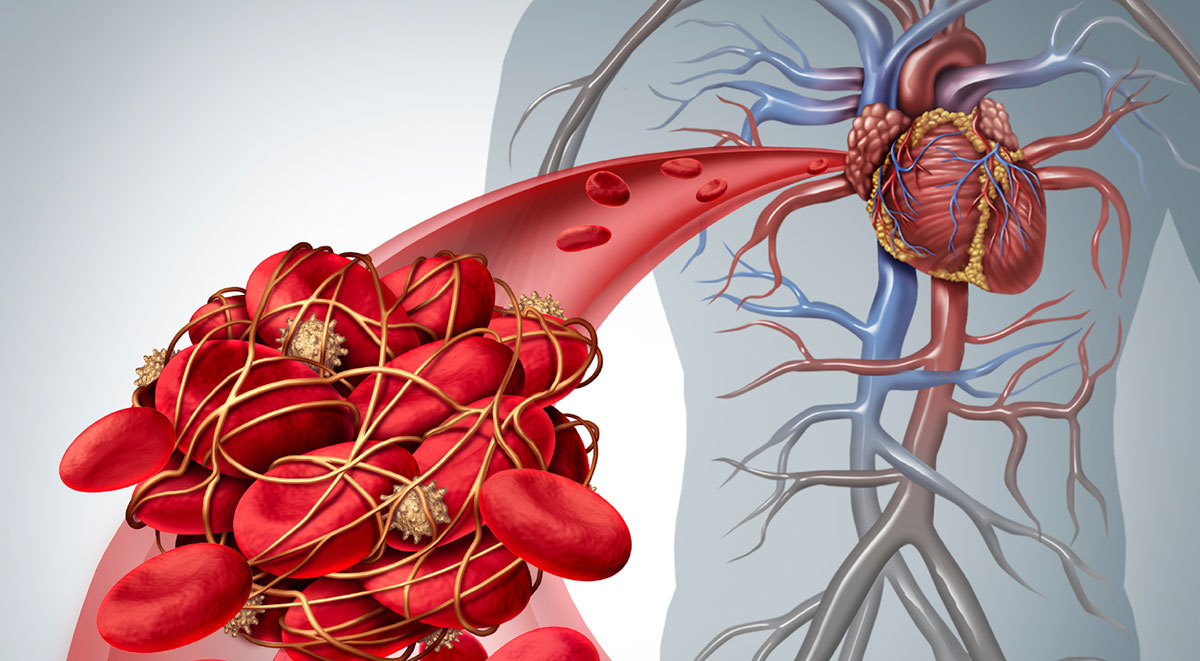

Xarelto, a “New Generation” anti-coagulant, was supposed to have been the ideal replacement for warfarin, the standard treatment for patients at risk for embolism and thrombosis due to blood clots.

The FDA approved Xarelto in 2011, and it was on pharmacy shelves by July of that year. However, within little over a year, the Institute for Safe Medication Practices (ISMP) was sounding the alarm about the abnormally high number of adverse events.

According to the report that was published in October 2012, there had been nearly 160 cases of serious side effects during the first three months of that year alone. Meanwhile, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration had reported an additional 360 such cases between the beginning of January and the end of April.

Those cases reported that Xarelto actually increased the risk of blood clots when the medication was discontinued, particularly in younger patients (65 years of age and under). Also known as rivaroxaban, this drug also increases the risk of fatal internal hemorrhaging as well as serious infections.

As a result, Johnson & Johnson faces over 15,000 lawsuits alleging that the company failed to warn doctors and patients about the associated risks. A significant number of plaintiffs are also alleging that the drug was inadequately tested before it was rushed through the approval process.

At this point, there is no antidote. Although a small California biotech firm, Portola, has been working on developing a reversal agent, that product has not yet received FDA approval. Currently, the only viable option for treatment of a Xarelto patient at risk for fatal bleeding is to administer emergency dialysis.

Despite the increasing number of lawsuits and growing number of adverse event reports, Johnson & Johnson spent a whopping $28.4 million in physician bribes during 2015 alone in order to get them to write prescriptions for Xarelto. In fact, that particular drug was at the top of ProPublica’s “Dollars for Docs” list for that year.

Of course, the pharmaceutical industry does not call such payments “bribes;” they are officially listed as payments for promotional speaking and/or consulting, travel and meals, gifts and royalties. Although members of the medical community deny that such payments affect their professional judgment when it comes to prescriptions, an analysis of ProPublica’s data shows that the more money a doctor receives from a drug company, the more likely s/he is to prescribe that company’s brand name products.